Let's settle this first: Anyone can make a white LED. The trick is making good white light—the kind that makes food look edible, fabrics rich, and doesn't fatigue your eyes by midday. That difference isn't in the chip; it's in the powdered magic dust we call phosphors. And at the heart of that dust are a few key rare earth ions. Here's what they really do on the production line.

The New Game: It's About Spectrum, Not Just Brightness

For years, the spec sheet only cared about lumens per watt. Now, lighting specifiers and OEMs are asking for TM-30 reports, high R9 values, and specific melanopic ratios for human-centric lighting. This isn't marketing fluff. It means your phosphor blend needs to fill the spectral holes that the classic "blue LED + YAG:Ce" combo leaves wide open, especially in the cyan (490nm) and deep red (650nm+) regions.

Failing here means your LEDs get rejected for high-end retail, museum lighting, or medical applications. The goal is a smooth, continuous spectrum—and that requires a cocktail of ions.

Breaking Down the Ion Toolbox: Ce³⁺, Eu, and Tb³⁺

Think of these as your primary colors in the light factory.

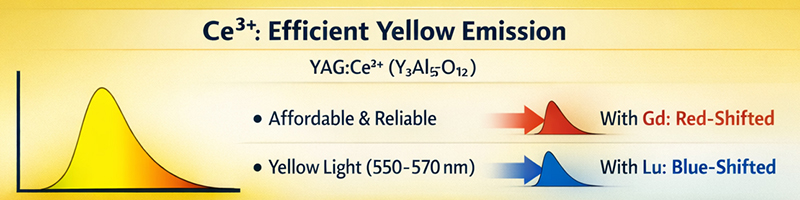

1. Cerium (Ce³⁺)

-

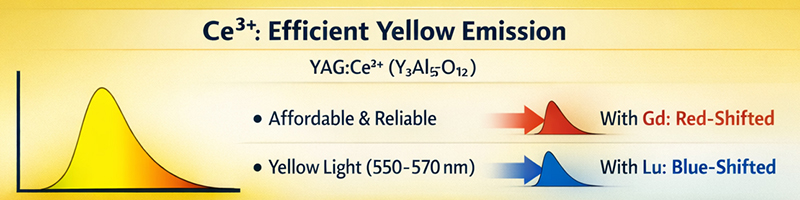

The Standard: In YAG, Ce³⁺ provides the efficient yellow emission. It's affordable, reliable, and widely used. But it's also why so many LEDs have that sickly, greenish tint and poor color rendering.

-

The Shift: The action now is in tuning the YAG lattice. By substituting Gadolinium (Gd) for Yttrium, you can red-shift the Ce³⁺ emission. More Lu? It blue-shifts. This lets you tweak the base yellow point without adding a new phosphor, saving cost and complexity. It's the first knob the engineers turn.

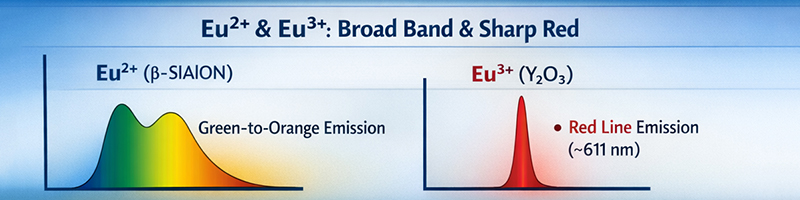

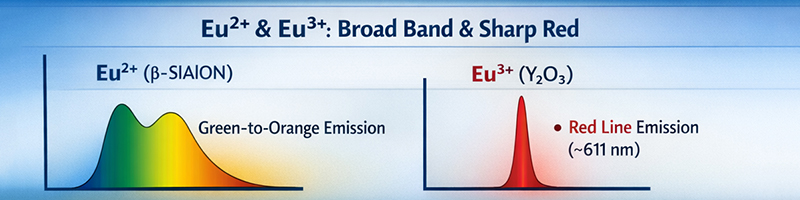

2. Europium (Eu²⁺ & Eu³⁺ )

This is where most blends fail or succeed.

-

Eu²⁺ in Nitrides (β-SiAlON): This is your green-to-orange broad band. It's expensive (those nitride syntheses aren't cheap), but it has brutal thermal stability. The key spec to check here is the FWHM (Full Width at Half Maximum). A wider FWHM fills more spectrum but can wash out saturation. It's a trade-off.

-

Eu³⁺ in Oxides (Y₂O₃): This is your sharp, saturated red line (~611nm). Forget R9—if you don't have a strong Eu³⁺ emitter, you'll never hit R9 >95. The problem? Its efficiency is lower, and it can be a reliability weak point if the host material isn't perfectly engineered.

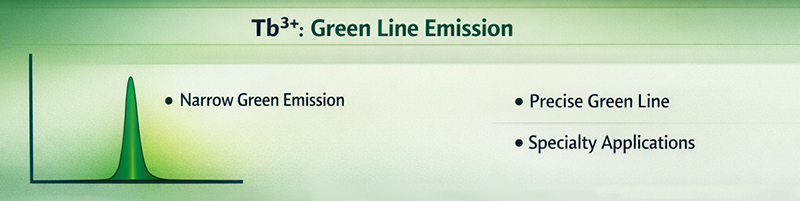

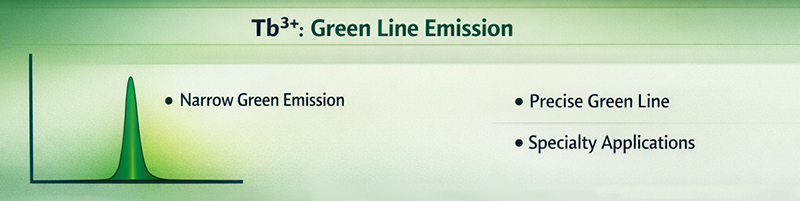

3. Terbium (Tb³⁺)

Tb³⁺ gives you line emission in the green. It's inefficient and costly, so you won't see it in general lighting. But if you're making a specialty LED for fluorescence microscopy or color calibration, where you need a specific, narrow green peak, Tb³⁺ is your only real option. It's a tool for very specific jobs.

Why the Host Crystal Is More Than Just a Backdrop

Where you put the ion is as important as the ion itself. This is materials engineering.

-

YAG: Think of it as a stable, gated community. The crystal field is strong and uniform, giving Ce³⁺ high efficiency and reliability. But it's rigid—hard to dramatically change the emission color.

-

Nitrides (like β-SiAlON): This is a tougher neighborhood with more "flex." The nitrogen-rich environment creates a different crystal field for Eu²⁺, pulling its emission into the vital green-red region. The synthesis is like high-pressure baking—costly but results in a material that doesn't fade in the heat of the LED junction.

-

Silicates: The affordable suburbs. Easier and cheaper to make, decent stability, but they start to fade (thermal quenching) when the LED junction gets really hot (>150°C). Fine for low-power bulbs, a liability for high-brightness COBs.

The Reality Check: "High Purity" Means Targeting Specific Impurities

On a supplier's CoA, "4N5" looks good. But which impurities? That's what matters.

-

Fe, Co, Ni ions are "killers." Even at 10 ppm, they act like little drains, sucking up the excitation energy and turning it into heat instead of light. Your brightness (QE, or Quantum Efficiency) drops directly.

-

Other rare earths are "poison." Put a bit of Praseodymium (Pr) in your Eu³⁺ red phosphor. Pr has its own absorption bands. It will steal some of the blue pump light meant for Eu³⁺, changing your color point and reducing output. Your blend becomes unpredictable.

-

The result of impurities: You have to use more phosphor to hit the same brightness and color point. More phosphor means higher light scattering, more backscatter loss into the chip, and ultimately, a less efficient, more expensive LED.

The Takeaway: Blending Light is a Precision Process

Choosing phosphors is no longer about picking a yellow and a red from a catalog. It's a system-level design problem balancing spectrum, efficiency, cost, and long-term reliability. The choice of ion and its host defines your performance envelope. The purity of the raw oxides determines whether you hit your targets consistently, batch after batch.

Struggling with CRI, efficiency, or color point consistency in your LED designs?

Send us your target spectrum or current blend challenge. Our team will analyze the ion-host combinations and provide a breakdown of how specific high-purity oxide grades (with guaranteed killer impurity levels) can tighten your performance and yield.